Welcome to the first edition of The Quack, my new monthly newsletter on disability and creativity! You may already know this if you’ve subscribed or found your way to this page, but if you don’t, allow me to introduce myself—I’m Katharine Duckett, a speculative fiction author and teaching artist with a long list of former lives (child actress, Peace Corps volunteer, and publishing professional, just to name a few).

In all of those incarnations, I was a disabled person. Whether I was navigating village life in rural Kazakhstan while teaching English with the Peace Corps or commuting from Brooklyn to the Flatiron Building in New York City when I worked in book publicity, I was inhabiting a body with a rare genetic cartilage growth disorder that causes chronic pain, the eventual need for joint replacements (I got both of my hips replaced just before I turned 30), and many other possible complications.

Disability has been part of my life since birth, and in fact influenced my existence before I ever showed up on the scene: multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, as my condition is known, was first diagnosed in my grandmother, though she suspects her father had it as well. My father and uncle also inherited it, though neither of my sisters did. Having this microcosm of disability history in my family has given me three generations of examples of the ways ableism plays out based on gender, class, sexuality, access to healthcare, and myriad other factors, which is something I’ll be exploring in future editions of this newsletter. It’s also made me keenly aware that sharing a disability does not mean sharing a homogenous experience: there are an estimated 1.3 billion disabled people in the world, which means there are at least 1.3 billion separate stories of what living with disability means.

That’s why I’m so passionate about promoting disabled storytellers—representations of disability are everywhere, but they’re often metaphors used by non-disabled people to signify hardship or to “inspire” a non-disabled audience. We need to amplify the voices of disabled creators, who are reckoning with discrimination, erasure, and often a lack of crucial resources—due to the correlation between disability, poverty, and unemployment—and who, despite all of this, are producing some of the most groundbreaking—and just really damn cool—art and media out there today.

Connecting Disability, Neurodiversity, and Creativity

I also want to use The Quack to delve deep into neurodiversity. Though I didn’t know it during those previous eras of my life, when I was trying to figure out employment, housing, and medical treatment as a disabled person, I was also moving through the world as a neurodivergent person. Getting diagnosed with ADHD at age 35 has added a new dimension to my understanding of disability and how my inability to fulfill normative societal roles always seemed to extend far beyond what I could or couldn’t physically do with my body. (Then there’s being queer—a whole other dimension of why I couldn’t fit into the tiny little boxes set up for me—but I’ll get to that and other intersections of identity that interact with disability and neurodivergence in future newsletters, too.)

Making space for the infinite complexity of human bodies and minds is at the heart of my writing. Whether it’s using critical analysis to expose underlying assumptions about what a person should be in popular media or exploring new realms of sentience in my speculative fiction, I’m always pushing to imagine worlds that are bigger, radically kinder, and more open to nuance and revolutionary possibilities for how we think about life and the universe than our own often seems to be.

I’ve contributed stories about disabled people leading the way into new futures in the anthologies Disabled People Destroy Science Fiction from Uncanny Magazine and Rebuilding Tomorrow: Anthology of Life After the Apocalypse from Twelfth Planet Press, both collections that featured work entirely by disabled and chronically ill creators. I also served as the guest editor for Uncanny’s Disabled People Destroy Fantasy issue. If I wasn’t aware of the breadth of talent and creativity in disabled and neurodivergent communities before, that slush pile (from which I could only select six stories—torture!) made it clear there’s an incredible range of untapped creative potential out there. We need to provide consistent, significant support to disabled and neurodivergent artists if we want to access these remarkable stories and change the landscape of exclusionary creative industries.

Disabled and neurodivergent people have some of the most relevant and revelatory insights to share when it comes to exploring questions of consciousness, embodiment, and how we structure our society and communities. I want to use this space to champion disabled, chronically ill, and neurodivergent creators, build community, and be in conversation with anyone who’s passionate, curious, or even good-heartedly confused about why it’s so crucial to center disability and neurodivergence when envisioning fictional worlds and reporting real-world narratives.

So tell me what you want to read in future installments of The Quack! I’ll always include a creative prompt for thinking more deeply about disability and neurodivergence in fiction and a disabled and/or neurodivergent artist to watch—check out those sections below. I’ll also be diving into disability representation in literature and media, examining the ways disabled and neurodivergent creators are subverting tired tropes and rejecting restrictive rules, and musing about related topics like the ways disabled and neurodivergent creators are remaking fairy tales and the function of disability in superhero narratives. Thanks for joining me and exploring the wide world of disabled and neurodivergent creativity!

Until the next Quack,

Katharine

Imagining Accessible Worlds: An Exercise

In February, I had the opportunity to speak at a virtual Disability Pride Week event organized by the wonderful Disabled Students’ Network at the University of St Andrews. My conversation partner was Becky Chambers, who writes acclaimed, universe-expanding fiction that exemplifies the ways science fiction and fantasy can help us radically rethink the structures of our worlds. I’m a huge fan of her funny, hopeful Wayfarers series, and an even bigger fan of the Monk & Robot series, which contains some of the most thoughtful, inventive world-building I’ve seen in speculative fiction. It’s one of those enthralling tales that burrows deep down into your heart and never leaves.

We talked about everything from the importance of centering disabled astronauts in space exploration (more on that to come in future newsletters) to the ways alien characters can help us think more expansively about accessibility and empathy (another great reason to check out Becky’s work, since she does this so well!). Afterward I co-led a brief workshop with the chair of the Disabled Students’ Network and shared the same writing prompt I’m going to give you here, which can be expanded in a number of ways if you want to continue exploring accessibility, disability, and world-building.

If you’re familiar with Deaf culture, you may know about Eyeth, “an imaginary planet for "people of the eye", in which everyone speaks in visual-manual modality (known as signing) unlike Earth where everyone speaks in vocal-auditory modality (speech).” I first learned about Eyeth in Sara Nović’s recent novel True Biz, where she describes it this way: “In the Deaf world, there’s a famous story of a utopian planet where everyone signs and everything is designed for easy visual access. In some tellings, hearing people are the minority and learn to confirm to the majority sign language, in others the planet is completely Deaf. […] Eyeth may be a pun, but it’s not a joke—it’s a myth.” A myth, she points out, that “reinforces Deaf culture as a culture. Storytelling and myths are an important part of what makes us human and a common thread across all kinds of ethnic groups.”

Nović goes on to include an Eyeth-related exercise for students, asking them to design Eyeth and imagine what Deaf-friendly architecture, technology, or other design elements they would include, as well as their plans for managing accessibility for a hearing visitor on Eyeth. Building on that, I want you to design, in detail, a world where a particular disability is centered. You can write, sketch, or use any other medium to conjure up your world, and I encourage you to think about all the facets of life—from public life to medical care to leisure activities—and the built environments that would be affected by this approach.

Prompt: Imagine a world where the majority—or all—of the inhabitants share a particular disability or form of neurodivergence. How would society function if structures, transportation, new technologies, modes of art, forms of recreation, et cetera were built around the disabled and/or neurodivergent people of this specific world? What accommodations would be necessary for visitors, or for those with multiple disabilities who might not be best served by the design of this society?

Next month, I’ll share a little bit about my insights from the workshop where we did this prompt, and the interesting ways the exercise began to evolve. If you’d like to share the world you built, feel free to send me your answers to this exercise, as well!

Artist to Watch: Molly Joyce

Composer and performer Molly Joyce uses disability as a creative source in her work, drawing on her own experience with disability and collaborating with artists across various fields to examine the realities, struggles, and joys of disabled life. Her ongoing project Perspective features disabled interviewees responding to the question of what various concepts like access, control, strength, and resilience mean to them. I’ve found the pieces, which you can listen to on her website or purchase for download, utterly mesmerizing—in the audio, Joyce layers the answers atop the sound of her electric vintage toy organ, an instrument she uses specifically because of the way it suits her body and engages her disability—and incredibly powerful, because it’s so rare to encounter a conversation where disabled voices are centered, let alone allowed to overlap, respond, amplify, and contradict each other, making room for the fullness of perspective disability can bring.

Check out more of Molly’s work on her website and take some time to experience this particular project. Many of the moments from this piece have stayed in my mind, but none more than these words from “What is connection for you?”: “Connection is why I’m a storyteller. Connection is the bridge.”

Coming Up

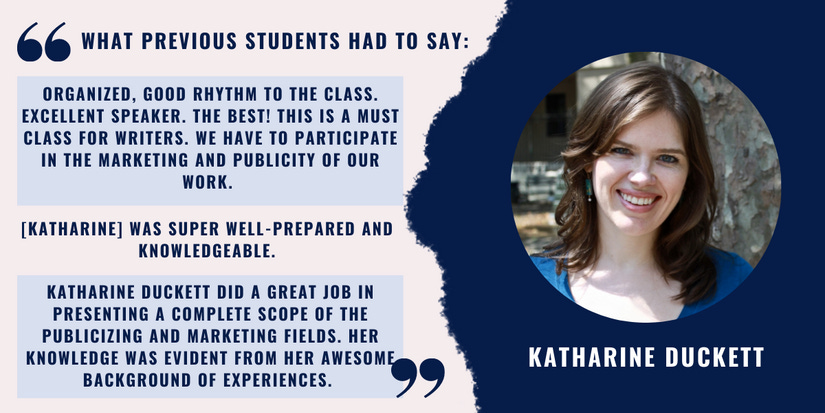

Are you an aspiring or published author who’s interested in learning more about coordinating marketing and publicity plans with your publisher and how best to promote your projects? Join me on June 7, 2023, from 6:30 PM to 9:30 PM CDT for “Marketing & Publicity for Authors: Working With Your Publishing Team,” an in-depth class from the Writers’ League of Texas on the timelines for short and long-term publicity and marketing strategies, the tools you can use to create your own sustainable, custom approach to author branding, and tips for building and managing relationships with the publishing professionals who are working on your book.

If you’re a disabled and/or neurodivergent author, I’d love to have you participate and ask any questions you may have about the specifics of working with a publishing team—I’ve worked on both sides of publishing, as a publicity manager and author, and think it’s particularly important that the publishing process be transparent, accessible, and inclusive for disabled and neurodivergent writers.

Nice introduction to this forum, Katharine! I’d like to hear (for a future edition) about well-known stories featuring disabled characters. Benjy from The Sound and the Fury, Lenny from Of Mice and Men, and Jake Barnes from The Sun Also Rises come to mind. Does their presence alone in the canon help or hurt? What about others? The books aren’t ABOUT disability, but it features prominently.